Understanding 3D Gaussian Splatting

an attempt to cover the knowledge gap

What exactly is this technique?

3D Gaussian Splatting is one of the solutions to the Novel View Synthesis problem.

Novel View Synthesis? That seems quite complicated, I don’t think this is my cup of tea.

Well, don’t stop reading just yet. Its not as contrived as it seems at first glance. Let’s start by understanding the literal meaning of the term ‘Novel View Synthesis’. It is made up of novel which means new, view is quite self-explanatory and synthesis means to combine different elements to make something new. So, the process goes something like this, we have a bunch of pictures of a room (say) and now we want to view the room from angles which were not present in the original set of pictures. To fulfill this desire of ours, we need to synthesize (make) these novel (new) views.

Now, there had been many attempts to solve the Novel View Synthesis problem but none of the attempts made for a convincing solution until 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) appeared in 2023. Let’s understand how it works!

Foundation

Before moving to the actual workings of 3DGS, let’s lay a firm foundational knowledge about gaussians.

1D Gaussian function

Starting off with 1D gaussian function, its general form is given as:

\[g(x) = \frac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{2\pi}} \exp \left( -\frac{1}{2} \frac{(x - \mu)^2}{\sigma^2} \right)\]Here, $\sigma$ is the spread of the gaussian and $\mu$ is the centre value of it. We query the function by substituting a value in place of the variable $x$.

Check out the visualisation below for a better understanding:

An interesting detail about 1D gaussians

Gaussian functions arise by composing the exponential function with a concave quadratic function (downward facing parabola)

\[f(x) = \exp(\alpha x^2 + \beta x + \gamma)\]where \(\alpha = -\frac{1}{2\sigma^2}, \quad \beta = \frac{\mu}{\sigma^2}, \quad \gamma = -\frac{\mu^2}{2\sigma^2} - \ln(\sigma \sqrt{2\pi})\)

2D Gaussian function

The 2D Gaussian function in our familiar form would look something like:

\[g(x, y) = A \exp \left( - \left( \frac{(x - \mu_x)^2}{2\sigma_X^2} + \frac{(y - \mu_y)^2}{2\sigma_Y^2} \right) \right)\]Here, $A$ is the amplitude, $\mu_x$, $\mu_y$ are the centers, and $\sigma_X$, $\sigma_Y$ are the spreads of the 2D gaussian in the $X$ and $Y$ axes respectively.

Again, a visualisation to help form a mental picture:

Notice that a 2D Gaussian is built by stacking ellipses on top of each other. The set of 2D points which result in the same output when plugged in the 2D Gaussian function lie on the same ellipse.

So, when a 2D Gaussian is sliced with a plane parallel to the $XY$ plane, we get an ellipse.

3D Gaussian function

As a natural extension to the 2D Gaussian’s definition, we get to the 3D Gaussian function which is given as:

\[g(x, y, z) = A \cdot \exp\left( -\frac{1}{2} \left( \frac{(x - \mu_x)^2}{\sigma_x^2} + \frac{(y - \mu_y)^2}{\sigma_y^2} + \frac{(z - \mu_z)^2}{\sigma_z^2} \right) \right)\]An alternate definition of a 3D Gaussian that is often seen in various place (eg. the 3DGS paper!) goes like:

\[f(x, y, z) = A \cdot \exp\left( -\frac{1}{2} (\mathbf{r} - \boldsymbol{\mu})^\top \Sigma^{-1} (\mathbf{r} - \boldsymbol{\mu}) \right)\]where:

$A = (2\pi)^{-3/2} \det(\Sigma)^{-1/2}$ is the normalization constant

$\mathbf{r} = [x, y, z]^\top$ is the position vector

$\boldsymbol{\mu} = [\mu_x, \mu_y, \mu_z]^\top$ is the center of the Gaussian

$\Sigma^{-1}$ is the inverse of the covariance matrix

How can these two definitions be equivalent?

I won’t give out a formal proof to establish their equivalence, but here’s a simple example to build an intuition about it.

We take $\Sigma$ to be a diagonal matrix:

\[\Sigma = \begin{bmatrix} \sigma_x^2 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \sigma_y^2 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \sigma_z^2 \end{bmatrix}\]then

then \(\Sigma^{-1} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{\sigma_x^2} & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \frac{1}{\sigma_y^2} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \frac{1}{\sigma_z^2} \end{bmatrix}\)

because for a diagonal matrix, the inverse is simply the reciprocal of each of the diagonal elements.

expanding $(\mathbf{r} - \boldsymbol{\mu})^\top \Sigma^{-1} (\mathbf{r} - \boldsymbol{\mu})$, we substitute $\mathbf{r} = [x, y, z]^\top$ and $\boldsymbol{\mu} = [\mu_x, \mu_y, \mu_z]^\top$

we get:

\[(\mathbf{r} - \boldsymbol{\mu}) = \begin{bmatrix} x - \mu_x \\ y - \mu_y \\ z - \mu_z \end{bmatrix}\] \[\Sigma^{-1} (\mathbf{r} - \boldsymbol{\mu}) = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{\sigma_1^2} & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \frac{1}{\sigma_2^2} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \frac{1}{\sigma_3^2} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} x - \mu_x \\ y - \mu_y \\ z - \mu_z \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{x - \mu_x}{\sigma_x^2} \\ \frac{y - \mu_y}{\sigma_y^2} \\ \frac{z - \mu_z}{\sigma_z} \end{bmatrix}\]now, \((\mathbf{r} - \boldsymbol{\mu})^\top \begin{bmatrix} \frac{(x - \mu_x)}{\sigma_x^2} \\ \frac{(y - \mu_y)}{\sigma_y^2} \\ \frac{(z - \mu_z)}{\sigma_z^2} \end{bmatrix} = \frac{(x - \mu_x)^2}{\sigma_x^2} + \frac{(y - \mu_y)^2}{\sigma_y^2} + \frac{(z - \mu_z)^2}{\sigma_z^2}\)

which looks like the term inside the exponential!

Equation for N-dimensional Gaussian function

\[f(\mathbf{x}) = \frac{1}{(2\pi)^{N/2} |\boldsymbol{\Sigma}|^{1/2}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2} (\mathbf{x} - \boldsymbol{\mu})^\mathsf{T} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}^{-1} (\mathbf{x} - \boldsymbol{\mu})\right)\]Here, $\mathbf{x}$ will belong to $\mathbb{R}^{N}$ and $\boldsymbol{\Sigma}$ will be of dimension $N \times N$

For 3D Gaussian, the $\Sigma$ matrix would look something like this:

\[\Sigma = \begin{bmatrix} \sigma_{xx} & \sigma_{xy} & \sigma_{xz} \\ \sigma_{xy} & \sigma_{yy} & \sigma_{yz} \\ \sigma_{xz} & \sigma_{yz} & \sigma_{zz} \end{bmatrix}\]where:

- the diagonal elements $(\sigma_{xx}$, $\sigma_{yy}$, $\sigma_{zz})$ represent the variances along the $x$, $y$ and $z$ axes.

- the off-diagonal elements $(\sigma_{xy}, \sigma_{xz}, \sigma_{yz})$ represent covariances between pairs of axes $(x, y, z)$.

A 3D Gaussian cannot be visualised the way we did for the other two lower dimensional Gaussians, because we cannot directly visualise a 4D space.

As an extension from the ellipse idea for 2D Gaussians, the set of 3D points which result in the same output from the 3D Gaussian function would lie on an ellipsoid. It can also be said that a 3D Gaussian is built from many ellipsoids where the larger ellipsoids enclose the smaller ones within them.

Nonetheless, here’s an illustration of an ellipsoid just to have a mental picture:

If we perform the eigenvalue decomposition of the $\Sigma$ matrix, we get:

\[\Sigma = Q \Lambda Q^\top\]where:

- $Q$: A matrix whose columns are the eigenvectors defining orientation of the ellipsoid wrt to the $x$, $y$ and $z$ axes.

- $\Lambda$: A diagonal matrix containing eigenvalues defining stretching along the $x$, $y$ and $z$ axes.

Key Idea

The general way to get novel view of any scene is to get a 3D representation of it, be it a mesh based, or point cloud based or a voxel based representation. Then using this 3D representation, render the scene from any viewpoint of your choice. This is basically like simulating the world (scene) inside our computers and then viewing it however we want.

The problem is that these 3D representations of a scene cannot be reliably estimated from just a bunch of pictures of the scene. This is where the magic of 3D Gaussian Splatting comes in!

Here, we represent the scene using 3D Gaussians. These Gaussians when projected and rendered on a 2D plane, give us a picture of the scene from a particular viewpoint. To be able to get a good picture of the scene from these Gaussians, the Gaussians are subjected to an interative optimization process. As part of the optimization process, we render the scene from the viewpoints for which we have the original images, and then take a photometric loss between the renderings and the original images.

Based on the difference between the renderings and the original images, we tweak the properties (what are these properties?) of the 3D Gaussians such that their difference is minimised.

Properties of a 3D Gaussian

The following are the properties attached with each of the 3D Gaussians in the 3DGS framework:

- 3D position ($\boldsymbol{\mu}$): A 3D vector which signifies the exact location where the 3D Gaussian is placed in space.

- Opacity ($\alpha$): Gives how much of the colour of this Gaussian influences the final image. An opacity value of $0$ means that the Gaussian is completely transparent i.e. it does not contribute anything to the final image and an opacity value of $1$ means that the Gaussian is completely opaque i.e. nothing behind it is visible in the final image.

- Anisotropic covariance ($\Sigma$): This gives the scale (size) and rotation (orientation) of the 3D Gaussian. It is called anisotropic because it is not symmetric in the three directions. An isotropic covariance having 3D Gaussian will just be a sphere with varying size (here, $\Sigma = k\boldsymbol{I}$).

- SH coefficients: These give the colour of the 3D Gaussian as a function of the viewing direction.

Projection of 3D Gaussians onto a 2D plane

The 3DGS paper directly hands out the following relation between the covariance of the 3D Gaussian ($\Sigma_{3D}$) and the 2D Gaussian ($\Sigma_{2D}$) obtained after projection:

\[\begin{gathered} \Sigma_{2D} = JW \Sigma_{3D} W^{T}J^{T} \\ \text{(yes, this cannot be used directly)} \end{gathered}\]We will now try to understand where this stems from instead of taking things just as given. Afterall, this is what researchers do!

This part is a little more involved than what we have seen so far but hang on and we will get through it.

An important property to know of about Gaussians is:

Let’s break down the above property step-by-step.

Affine transformations are of the following form:

\[f(\vec{x}) = A\vec{x} + \vec{b}\]And when Gaussian functions are subjected to an affine transformation, this again results in a Gaussian function. Hence, they are called closed under affine transformation.

Don’t believe me? Here’s the proof for you.

We re-write the affine transformation as: \(\vec{x} = A^{-1}(\vec{y} - \vec{b})\)

Then we substitute this in the equation for 3D Gaussian:

\[\begin{align*} Q(\vec{y}) &= \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2} \left(A^{-1}(\vec{y} - \vec{b}) - \vec{\mu}\right)^T \Sigma^{-1} \left(A^{-1}(\vec{y} - \vec{b}) - \vec{\mu}\right)\right) \\ &= \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2} \left(A^{-1}(\vec{y} - (A\vec{\mu} + \vec{b}))\right)^T \Sigma^{-1} \left(A^{-1}(\vec{y} - (A\vec{\mu} + \vec{b}))\right)\right) \\ &= \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2} \left(\vec{y} - {\color{blue}\underbrace{(A\vec{\mu} + \vec{b})}}\right)^T {\color{purple}\underbrace{A^{-T} \Sigma^{-1} A^{-1}}} \left(\vec{y} - {\color{blue}\underbrace{(A\vec{\mu} + \vec{b})}}\right)\right) \\ &= \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2} (\vec{y} - {\color{blue}\vec{\mu}'})^T {\color{purple}\Sigma'} (\vec{y} - {\color{blue}\vec{\mu}'})\right) \end{align*}\]See, even after applying the affine transformation, we end up with an equation for a Gaussian. Albeit with a different centre and covariance matrix (the transformation had to do something right?).

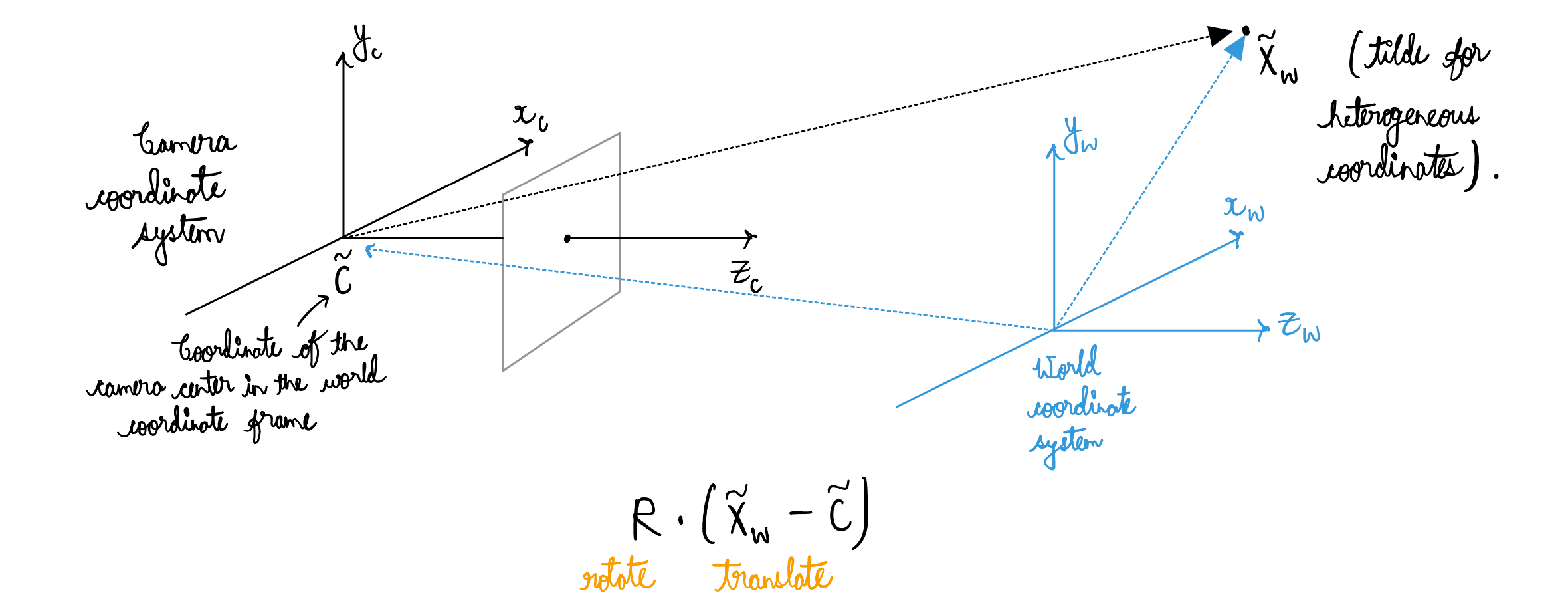

You might remember seeing the following kind of illustration back in your computer vision class. This shows the need for world-to-camera coordinate system transformation.

To simplify our case of projecting 3D Gaussians onto a 2D plane, we will consider that there is no translation involved in going from the world coordinate system to the camera coordinate system and just a rotation gets the job done.

We define the viewing transformation $W$ as the transformation which gets us from the world space to the camera space.

Now, we apply the viewing transformation onto the 3D Gaussian function:

\[G(\vec{x}) = \exp\left\{-\frac{1}{2} (W\vec{x} - W\vec{\mu})^T (W\Sigma W^T)^{-1} (W\vec{x} - W\vec{\mu})\right\}\]How can we directly apply the viewing transformation on the covariance matrix? Isnt it meant for a point?

The covariance matrix is given as:

\[\Sigma = E[(\vec{x} - \vec{\mu})(\vec{x} - \vec{\mu})^{T}]\]After applying the transformation $W$ on the vector $\vec{x}$:

\[\begin{align} \vec{x'} &= W\vec{x} \\ \vec{\mu'} &= W\vec{\mu} \end{align}\]Now,

\[\begin{align*} \Sigma' &= E\left[(\vec{x}' - \vec{\mu}')(\vec{x}' - \vec{\mu}')^T\right] \\ &= E\left[(W(\vec{x} - \vec{\mu}))(W(\vec{x} - \vec{\mu}))^T\right] \\ &= E\left[W(\vec{x} - \vec{\mu})(\vec{x} - \vec{\mu})^T W^T\right] \end{align*}\]$W$ is a constant transformation matrix. Hence, can be directly taken out from the expectation expression.

\[\begin{align*} \Sigma' &= W {\color{blue}{\underbrace{E\left[(\vec{x} - \vec{\mu})(\vec{x} - \vec{\mu})^T \right]}}} W^T \\ &= W {\color{blue}\Sigma} W^{T} \\ \end{align*}\]This justifies our application of the viewing transformation directly on the covariance matrix.

We now define the following terms in the camera space which will be come in handy in a while:

\[\begin{align*} \vec{x'} &= W\vec{x} \\ \vec{\mu'} &= W\vec{\mu} \\ \Sigma' &= W \Sigma W^{T} \end{align*}\]The Gaussians are to be projected in the camera space onto the $z=1$ plane, and the projection function $\varphi$ is defined as (cite the paper):

\[\varphi(\vec{x'}) = \vec{x'} (\vec{x_0}^{T} \vec{x'})^{-1} (\vec{x_0}^{T} \vec{x_0}) = \vec{x'} (\vec{x_0}^{T} \vec{x'})^{-1}\]where $\vec{x_0} = [0, 0, 1]^{T}$ represents the projection of the camera space’s origin onto the $z=1$ plane.

I myself don’t have an intuitive understanding of the above projection function but for the $z=1$ plane case, this gets simplified in a pretty understandable form:

\[\varphi(\vec{x}') = \vec{x'} \underbrace{ (\vec{x_0}^T \vec{x'})^{-1} }_{\substack{\downarrow \\ \frac{1}{Z}}} \underbrace{ (\vec{x_0}^T \vec{x_0}) }_{\substack{\downarrow \\ 1}}\]And this is simply equivalent to:

\[\begin{bmatrix} x \\ y \\ z \end{bmatrix} \rightarrow \begin{bmatrix} x/z \\ y/z \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}\]Another important property to take note of:

We want to get to get a 2D Gaussian after projection of 3D Gaussian onto the image plane. Hence, we take an affine approximation of the projection function using the Taylor’s series expansion:

\[\begin{align*} \varphi(\vec{x'}) &= \varphi(\vec{\mu'}) + \frac{\partial\varphi}{\partial\vec{x'}}(\vec{\mu'})(\vec{x'} - \vec{\mu'}) + R_1(\vec{x'}) \\ &\approx \varphi(\vec{\mu'}) + \frac{\partial\varphi}{\partial\vec{x'}}(\vec{\mu'})(\vec{x'} - \vec{\mu'}) \end{align*}\]This gives us:

\[{\color{myPink} \varphi(\vec{x}') = \varphi(\vec{\mu}) + {J}(\vec{x}' - \vec{\mu}') }\]where ${J} = \frac{\partial\varphi}{\partial\vec{x’}}(\vec{\mu’})$ is the Jacobian of the affine approximation of the projective transformation.

Applying this approximated projection function to the 3D Gaussian’s function:

\[\begin{align*} G_{2D}(\vec{x'}) &= \exp\left\{-\frac{1}{2} ({J}\vec{x'} - {J}\vec{\mu'})^T ({J} \Sigma' {J}^T)^{-1} ({J}\vec{x'} - {J}\vec{\mu'})\right\} \\ &\approx \exp\left\{-\frac{1}{2} (\varphi(\vec{x'}) - \varphi(\vec{\mu'}))^T ({\color{purple}\underbrace{J \Sigma' {J}^T}_{\substack{\downarrow \\ \Sigma_{2D}}}})^{-1} (\varphi(\vec{x'}) - \varphi(\vec{\mu'}))\right\} \end{align*}\]Comparing the above equation with that of a standard Gaussian equation, we get the relation for the covariance of the 2D Gaussian ($\Sigma_{2D}$).

\[\Sigma_{2D} = J \Sigma' {J}^T = J W \Sigma W^{T} J^{T}\]Now, $\Sigma_{2D}$ must be a $2 \times 2$ matrix as it the covariance matrix of a 2D Gaussian. However, the right hand side of the above equation gives out a $3 \times 3$ matrix.

What’s at play here?

If you have read the paper, you might know that we need to discard the last row and column of the obtained $3 \times 3$ matrix to get our desired $2 \times 2$ covariance matrix.

Again, we cannot accept anything just because we were told so. Let’s try getting a better intuition for what’s going on.

We have the following defined:

\[\begin{align*} \text{A point } \vec{x'} &= [x, y, z]^T \\ \text{Gaussian's centre } \vec{\mu'} &= [\mu_x, \mu_y, \mu_z]^T \\ \text{The projection formula } \varphi(\vec{x'}) &= \begin{bmatrix} x/z \\ y/z \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} \end{align*}\]The expanded Jacobian matrix would look like the following:

\[J = \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial \vec{x'}}(\vec{\mu'}) = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial(x/z)}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial(x/z)}{\partial y} & \frac{\partial(x/z)}{\partial z} \\ \frac{\partial(y/z)}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial(y/z)}{\partial y} & \frac{\partial(y/z)}{\partial z} \\ \frac{\partial(1)}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial(1)}{\partial y} & \frac{\partial(1)}{\partial z} \end{bmatrix}_{\text{at } \vec{x'}=\vec{\mu'}} = \begin{bmatrix} 1/\mu_z & 0 & -\mu_x/\mu_z^2 \\ 0 & 1/\mu_z & -\mu_y/\mu_z^2 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\]Notice that the rank of the $J$ matrix is $2$ due to the third row being entirely zeros.

Coming back,

\[\Sigma_{2D} = J \Sigma' J^{T} = \begin{bmatrix} 1/\mu_z & 0 & -\mu_x/\mu_z^2 \\ 0 & 1/\mu_z & -\mu_y/\mu_z^2 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \sigma'_{11} & \sigma'_{12} & \sigma'_{13} \\ \sigma'_{21} & \sigma'_{22} & \sigma'_{23} \\ \sigma'_{31} & \sigma'_{32} & \sigma'_{33} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 1/\mu_z & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1/\mu_z & 0 \\ -\mu_x/\mu_z^2 & -\mu_y/\mu_z^2 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\] \[\implies \Sigma_{2D} = J\Sigma'J^T = \begin{bmatrix} \sigma_{11} & \sigma_{12} & 0 \\ \sigma_{21} & \sigma_{22} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\]$\Sigma_{2D}$ is the covariance matrix of the new shape in 3D space. But the zeros in the third row and column tell us that there is zero covariance in the 3rd dimension (the z-axis). This makes perfect sense, we flattened the Gaussian onto a 2D plane, so it has no ‘thickness’ or variation along the z-axis anymore. Hence, we can skip the last row and column to get our final $2 \times 2$ covariance matrix $\Sigma_{2D}$ for the 2D Gaussian.

Way forward

We still haven’t covered some topics such as $\alpha$ blending and Spherical Harmonics. I myself am learning about these and will update the page when I have a good understanding of those. See you soon!